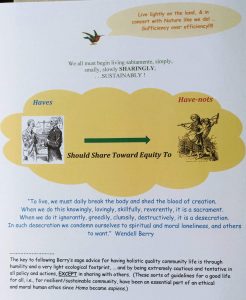

“To live, we must daily break the body and shed the blood of Creation. When we do this knowingly, lovingly, skillfully, reverently, it is a sacrament.

When we do it ignorantly, greedily, clumsily, destructively, it is a desecration. In such desecration we condemn ourselves to spiritual and moral loneliness, and others to want.” Wendell Berry (2003)

As I enjoyed tennis matches with seven gracious women on one cool (ca. 70 degrees F) fall morning at Starcke Park here adjacent to the Guadalupe River in Seguin, Texas, a cute little fall webworm crawled across the court. Like my attitude toward ants and spiders and most life forms, I felt admiration and respect for this little fuzzy critter, and I took care to let it continue in its seemingly focused journey toward further enjoyment of life.

Nevertheless, I am not reluctant to kill a “lowly” cockroach. I have been conditioned to immediately think of cockroaches as despicable when I detect one or more of these creatures, and I will not rest until I believe they are eradicated from my home. But this tough attitude toward blattids does stop in my abode! In Seguin there is a restaurant which has an excellent reputation for good tacos. I currently do not give this place my business because I saw a German cockroach on its vending-counter some five-plus years ago.

I suppose the only other organisms for which I have such a “genocidal-attitude” are rats and mice. My disdain for these creatures is not unlike that toward cockroaches; I absolutely do not want these creatures moving into my household or attached environment in which I live and work.

Other killings I have done for which I feel truly little guilt are those committed against screwworms (New World species) early in my life. Perhaps, I have lived a somewhat sheltered life, but the most gruesome experiences I have had in my ca. 73-plus years were screwworm-infested cattle heads, calf navels, and pig scrotums. As a young side-kick of and laborer for my father in the 1950’s and 60’s, I helped him doctor, or doctored myself, many wounds in hogs and cattle which were infested with this flesh-eating insect parasite with the black Smear-62 screw-worm killer or EQ-335 (or rarely an aerosol with lindane as an active ingredient).

During my freshman year (1960-61) at Devine High School in vocational agriculture, I participated in a Future Farmers of America-Greenhand Farm Radio contest in which our topic was the proposed screwworm-eradication program for the southwestern U.S., or basically Texas. We discussed the biology of the screwworm, the promising sterile insect technique for eradication of this insect, and a proposed beef cattle check-off program to fund the eradication program.

By the time I graduated from high school in 1964 the screwworm was declared eradicated from Texas. During my high school years Dr. E.F. Knipling’s eradication program using airplane releases of irradiated and sterilized screwworms, which had been raised at an old Air Base in Mission, Texas, had been in high gear. (There was a resurgence of screwworms in the 1970’s reported to me from back home by my brothers while I was working on my doctorate in entomology at the University of Florida, and I was fortunate to be able to attend a fabulously informative international conference in Gainesville, FL, addressing the population dynamics of field populations and challenges which had arisen with genetic changes (micro-evolution) and quality control of lab-reared screwworms. We still have screwworms in South America, and there have been recent outbreaks of New World screwworms in North Africa and the Florida Keys. The outbreaks in Africa and the Keys have been subsequently snuffed out!)

Now, concerted efforts to eradicate species like screwworms back in the 1950’s and 60’s, but even up until current times, which were considered to be immensely pestiferous, were done, relatively speaking, without much adherence to the Precautionary Principle. Moreover, in their 1998 review of eradication and pest management, J.D. Myers et al. stated, “Cost-benefit analyses of eradication programs involve biases that tend to underestimate the costs and overestimate the benefits.1” Anyway, the screwworm eradication effort was steamrolled through by E.F. Knipling in his powerful leadership role in USDA entomological research. It did employ many of my colleagues in entomology from the southwestern U.S. and was a successful program in the southeastern and southwestern U.S., Mexico, and Central America. In 1980, as a young research scientist and coordinator of a fall armyworm conference, I had the pleasure of being invited to share some Wild Turkey whiskey with the stately and venerated and very knowledgeable and kind, Dr. Knipling in his hotel room in Biloxi, MS, and of discussing, one on one, his proposed talk on area-wide strategies of integrated pest management, including biological control. … Dr. Knipling, who died at 90 years of age, was 71 or about my current age at the time.

To reiterate in summary, the screwworm, a mostly tropical species, was relatively easy to eradicate from North America, and the detrimental ecological consequences were probably relatively minor because of the generally low densities and relatively small biomass of the species. Therefore, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, we did not ponder too long upon the Precautionary Principle before deciding to eradicate the screwworm.

Another species with which we have been successful in eradicating is the cotton boll weevil. We are close to eradicating this late 19th century/early 20th century invader species from most cotton-growing areas of the United States. And, even though eradication strategies have employed the use of widespread applications of biocides along with other tactics, for the long-term there will be a probable dramatic net reduction in the use of biocides for cotton production in the U.S. The boll weevil is a key pest of cotton, and when broad-spectrum biocides have been used for its control, the detrimental impact on parasitoids and predators of the cotton bollworm and other insects has resulted in a number of secondary pests, including the cotton bollworm.

Decisions to eradicate some invasive species (but generally not “invasive” agricultural crop-species and domesticated animals), resulting from the Columbian Exchange, which University of Texas’ esteemed professor, Alfred Crosby, labeled “Ecological Imperialism,” seem to be easier to make than the examples I have chosen to be presented herein because of my own lifetime experiences. This is especially so for exotic invaders of islands.

However, the situation is quite different for many species, e.g., when contemplating eradication of a mosquito species or even some particular populations of these pesky piercing-sucking feeders. Despite the serious health challenges caused for humans by mosquitoes, the huge numbers and biomass of mosquitos in symbioses2 (i.e., “nature”), and their role as key components of important food webs and biodiversity cause us to think at least twice when we ponder eradication of even Aedes aegypti, vector of so many human diseases, or Anopheles mosquitoes, vectors of dreaded malaria.

(I do wish to insert at this point, that I am in accordance with the famous sea turtle biologist, Archie Carr, who taught me much about community ecology, in stressing that we should for the most part leave snakes, including rattlesnakes, and spiders, scorpions, wasps, and bees, etc. alone. Let them be!)

Shifting to another level or aspect of killing, as is the case with most humans, I have slaughtered many plants for various reasons over my lifetime. However, because we generally share less than 60% of our respective genes, we are not empathic to their feelings and consciousness. Moreover, because they and other primary producers are what we depend upon, directly or indirectly, for the matter and energy resulting in human life, this slaughter of plant lives does not cause much distress for us. We will swear off eating of our dear animal kin but never swear off killing and ingesting all life forms … or dear animal, dear plant kin, AND loveable ones of other phyla. (Obviously, deciding to abstain from killing and eating all the various dear life forms would be to commit suicide.)

The fact is, however, that the heavy load on the ecosphere of humans and their domesticated species is an effective killer of “climax” vegetation and communities and symbioses, or “nature,” to the extent that it might be immoral and unethical. Nevertheless, proper rangeland management and the utilization of grass-fed beef, browsers, and free-range animals as food is much more appropriate than feedlot-confined or caged domesticated animals. In addition, maintenance of rangeland systems results in less destruction and chaos in symbioses than plowing these systems out for wheat and other small grain production systems. These more natural rangeland systems of food production result in the killing of less soil biota and other biota and the realization of much more biodiversity–than grain, vegetable and most fruit and nut production systems. (By the way, the Land Institute, Salina, Kansas is working steadily and vigorously to improve current monoculture-systems of grain with breeding and development of perennial grain-, oil-, and legume-crops, which might be utilized in more diverse intercropping systems involving less tillage and less synthetic fertilizers and biocides. https://landinstitute.org/about-us/ )

Now, we are going to have to continue to kill to healthily survive as human individuals, demes, and populations and to survive as a species. But where do we draw the line of killing in these and other aspects of living/killing systems? When we attempt to put all into perspective, it is generally not an easy task to make these killing decisions. On the other hand, war and capital punishment, for example, are de facto premeditated acts of murder of living lived lives and have no moral or ethical currency.

Decisions concerning conventional birth control are not so clear-cut. Human birth control can be effective in reducing growth in populations of Homo sapiens, which generally results in more resources and habitat for all others. When one individual, deme, or population dominates an inordinate amount of energy, matter, food, or habitat, this action inevitably results in killing of other lifeforms, including other humans, or the prevention of adequate matter and appropriate energy transformation for future living beings. But depending on the type of birth control, it may also result in the killing of a partial sperm or ovum or of a developing human zygote or embryo. Moreover, human living systems do provide resources and habitat for some particular species.

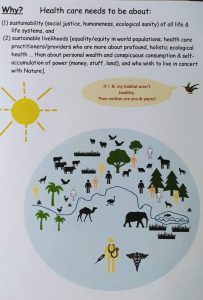

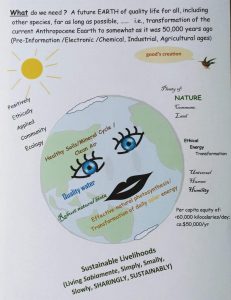

The somewhat arbitrary3 lines to effectively reduce killings, which I posit are developed in the illustrations in our little book on applied ecology, lighten the ecological footprint and reduce embodied human-appropriation of net primary productivity. The immensely powerful must share that power with the relatively powerless, poor, and disenfranchised. Realize per capita equity of <70,000 kilocalories/day and perhaps ca. <$50,000/year.

Finally, increase in unsustainable jobs, GDP, the power of the military-industrial complex, human and domesticated animal numbers, and the corresponding rampant human development and artificialization of what was a robust and healthy symbioses are indicators of and processes of a killing global-machine.4 To slow down this killing5 we desperately do need to live by the mantra of “Sabio, Simple, Small, Slow, Steadfast, Sharing, SUSTAINABLE.”

(Perhaps readers of this piece will begin to understand why I had feeling of total sickness upon the election of Donald Trump and why I have generally felt sicker ever since. Trump and his policies are the antithesis of a process toward a healthier symbioses and a healthier humanity.)

In slightly paraphrasing Wendell Berry, when we break the body and shed the blood of creation knowingly, lovingly, skillfully, reverently, it is a sacrament. When we do it ignorantly, greedily, clumsily, destructively, it is a desecration.

pbm

( 7 S’s / VV->^^ )

……………………………………..

1 Myers, J.H. et al. 1998 Eradication and pest management. Annual Rev. of Entomology. 43. 471-91

2 I do realize that I lose some readers and risk a reduction in communicating when I use some of these specialized ecological terms. Nevertheless, I feel strongly that we need these terms in our lexicon to communicate, develop, and grow toward consilience and empathy and begin to collectively develop sustainable community.

3 Actually the <70,000 kilocalories/capita/day originally came from a napkin calculation to keep a world of 9-11 billion at a similar energetics level to, or just below, what it is today with ca. 8 billion humans.

4 There are numerous systems to realize indicators of sustainability which have been proposed and researched. Five indicators that might rise to the top are: the Gini coefficient, embodied human appropriated net primary productivity, ecological footprints and biocapacities, embodied kilocalories “used”/per capita/day, and soil sealing per capita. However, there are many others of importance.

5 Recent scientific reports indicate global insect numbers are falling dramatically on this Anthropocene Eaarth. As an example, a study in 2017 “showed a 76 percent decrease in flying insects in the past few decades in German nature preserves. “ SA Express-News October 16, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2017/10/18/this-is-very-alarming-flying-insects-vanish-from-nature-preserves/?utm_term=.347d50c3395

You raise some interesting points and have me pondering my role in death and killing. Interesting.